Preliminary Reflections on Post-Assad Syria: Emerging Dynamics and the Complex Reality of Refugee Returns from Türkiye

by: Umutcan Yüksel, N. Ela Gökalp-Aras | Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul (SRII)

On December 8, 2024, Syria witnessed a transformative moment when armed rebels, predominantly led by ’Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), gained control of Damascus, leading to President Bashar al-Assad’s departure from the country. This development, marking the end of a 14-year civil war, has created a complex mixture of hope and uncertainty among Syrian refugees, including the 2.9 million living under temporary protection in Türkiye. While the political transition suggests possibilities for a return, the reality on the ground reveals a more nuanced situation where security concerns, infrastructure challenges, and practical considerations heavily influence refugee decision-making.

The scale of Syria’s displacement crisis remains staggering. More than half of the pre-war population has been displaced, with over 13 million Syrians forced from their homes since 2011. Of these, 7 million remain internally displaced within Syria, while more than 6 million have sought refuge in neighbouring countries, Europe and beyond. Recent regional developments have further complicated this landscape, with over half a million people entering Syria from Lebanon in late 2024 due to Israeli airstrikes, while simultaneously, over 1.1 million Syrians faced new internal displacement between November and December 2024.

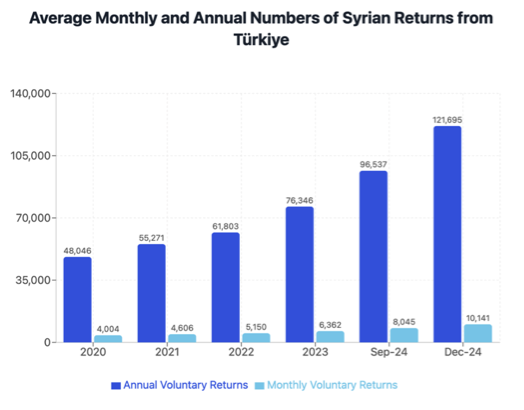

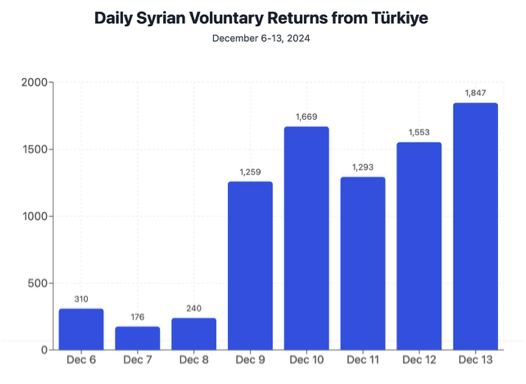

Since 2016, approximately 737,000 returns have been recorded from Türkiye, including 22,000 between September and December 2024. As seen in the Figure 1, this reflects a gradual increase over the years, particularly due to the various push and pull factors (such as Turkish military interventions in Northwest Syria, deteriorating socio-economic conditions, policy shift regarding the access to territory and registration, increase in the anti-refugee sentiment, etc.). While this was representing around 200-300 people returning per day in the pre-fall of Assad period, Minister Yerlikaya noted that over the past few days, an average of 1,100 to 1,150 Syrians has been returning voluntarily each day. As seen in the Figure 2, a stark increase in returns over the days was observed since the fall of Assad. But this also suggests that political change alone does not automatically trigger large scale organized returns. Instead, refugees are carefully weighing multiple factors in their decision-making process.

Figure 1: Average monthly and annual numbers of Syrian returnees from Türkiye, Source: AHaber (September 2024) & TBMM (December 2024)

Figure 2: Daily number of Syrian returnees from Türkiye since the fall of Assad, Source: Official Statement of Minister of Interior

Under the Turkish Temporary Protection Regulation (TPR, 2014), Syrians wishing to undertake voluntary return must follow specific administrative procedures. First, they must apply at the relevant Provincial Directorate of Migration Management (PDMM), where they fill out and sign a “voluntary return form.” After completing the form, they proceed to the border crossing of their choice. At the border, Turkish authorities verify the individual’s identity and conduct checks for any criminal records or outstanding obligations, such as unpaid taxes. If no issues arise, the individual’s temporary protection status in Türkiye is cancelled, and their temporary protection identification card is collected and destroyed. A v-87 restriction code is added to the cancelled ID, including bio-data and returnee fingerprints. Once the return is finalized, the person is no longer under Türkiye’s temporary protection regime. Returns are taken through different border gates. UNHCR is monitoring return interviews in 12 provinces and at five border crossing points in the southeast. Government processing of voluntary returns continues within provinces and at six border crossings: the five in the southeast monitored by UNCHR as well as Akçakale/Tel Abyad.

Based on the return interviews monitored by UNHCR since the fall of Assad, more than one-third of returnees are individuals returning alone due to the absence of dependent family members in Türkiye or the intent to assess conditions in Syria before facilitating their family’s return. Some female-headed households are among the returnees. These individuals typically return first to assess security conditions, survey the state of their homes and businesses, and set up living arrangements before potentially encouraging the rest of the family to follow. Women and children are present among returnees, but to a much lesser extent at this initial stage. While economically stable individuals and those with professional backgrounds in Syria show higher return inclinations, other groups demonstrate more hesitation. Families with school-age children, refugees of Kurdish origin, single-parent female households, and university students are generally more reluctant to return. These variations reflect how different groups assess risks and opportunities based on their circumstances and vulnerabilities.

This pattern is influenced by the pragmatic need to inspect living conditions in Syria after years of conflict. Many Syrian families in Türkiye have expressed a similar strategy—sending one adult male family member ahead to prepare the home environment and assess feasibility. Only once basic needs and safety are secured do the rest of the family members contemplate returning. This cautious approach helps explain why large-scale, immediate voluntary repatriations have remained relatively limited despite the possibility of return. In the event that a Syrian who has voluntarily returned to Syria decides to re-enter Türkiye, the re-issuance of temporary protection status is not guaranteed. Instead, the authorities review the individual’s circumstances on a case-by-case basis. This reflects the principle that once a Syrian refugee opts for voluntary return, regaining temporary protection in Türkiye is contingent on administrative discretion and a re-assessment of protection needs.

The current framework does not allow for “go-and-see” visits, which were previously permitted under special holiday provisions. Unlike the past practice that allowed short, temporary visits during religious holidays, today’s system views any return as a voluntary and final move. Thus, a Syrian who returns voluntarily is expected to remain in Syria. Subsequent re-admission into Türkiye under temporary protection would require a new assessment and is not guaranteed.

Return Environment in the Post-Assad Period

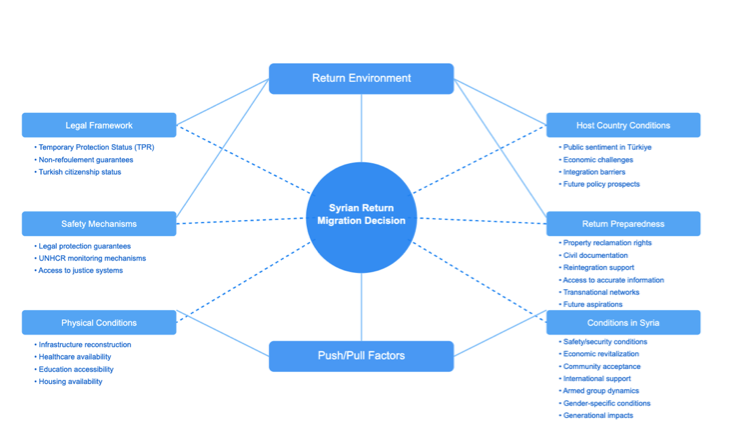

The post-Assad landscape presents substantial challenges that directly impact return decisions. Figure 3 illustrates how these decisions are shaped by both the return environment and push/pull factors. Safety and security remain primary concerns, with the presence of multiple armed groups, risks of retaliation from former regime supporters, and widespread landmine contamination. The devastation of basic infrastructure presents another critical barrier - 14 years of conflict have severely compromised housing, electricity, water, sanitation, healthcare, and education systems. For refugees who have adapted to relative stability and access to services in Türkiye, these deficits represent significant deterrents to return.

Figure 3: Return environment and push/pull factors determining the return decisions of Syrians

Legal complications further influence return decisions. Property rights restitution, compensation mechanisms, the replacement of lost documentation, and the documentation of Syrians who were borne aboard remain complex challenges. The decision to return also has significant legal implications for refugees’ status in Türkiye. Current regulations stipulate that those who return to Syria forfeit their temporary protection status. This irreversible loss of legal status creates additional pressure on refugees to make fully informed decisions before committing to return.

The temporary nature of protection for Syrians in Türkiye, governed by the Temporary Protection Regulation (TPR), is a significant source of uncertainty and precarity, especially for those unwilling or unable to return to Syria. The legal basis for the annulment of temporary protection is based on Article 11 of the TPR. Accordingly, it can be terminated at a group or individual level if the reasons for granting temporary protection no longer exist (e.g., improved conditions in the country of origin) and if the Presidency decides to end the temporary protection status. Annulment of temporary protection does not automatically lead to deportation due to the non-refoulement principle, but individuals may be left without a clear legal status if alternative protections, such as international protection, are not pursued or granted. Although voluntary returns have significantly increased after December 8, some Syrians will not want to return not to lose their TP.

To guarantee the success and sustainability of refugee returns, legally binding agreements must address critical aspects of safety, justice, equity, and collaboration. Agreements between host countries, emerging Syrian authorities, and international bodies must enshrine clear legal guarantees for the safety of returnees. These guarantees must ensure protection from persecution, arbitrary detention, or retaliation.

Central to these agreements is an explicit commitment to the principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits returning individuals to places where they face threats to their life or freedom. Compliance with international humanitarian law is imperative to ensure the humane treatment of returnees. An agreement must establish independent monitoring mechanisms led by organizations such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or similar international bodies. These mechanisms should oversee adherence to the terms of the agreement, monitor human rights conditions, and ensure that returnees are not exposed to insecurity or injustice. Independent monitoring helps build trust among returnees and host countries alike. A legally binding agreement must emphasize equal treatment of all returnees, irrespective of their ethnic, religious, or political backgrounds. This is crucial to prevent the marginalization or targeting of specific groups, which could reignite tensions and conflict, thereby creating new cycles of displacement. Equal treatment also fosters a sense of national unity and reconciliation. Agreements must provide returnees with clear avenues to access justice and remedies in the event of violations. The responsibilities of all stakeholders, including host countries, international organizations, and donor nations, must be clearly defined within the agreement. These responsibilities should encompass funding reconstruction, providing transportation, and facilitating reintegration programs for returnees. A fundamental component of any agreement must be a commitment to voluntary returns. Refugees should be empowered to make informed decisions about returning based on credible information regarding conditions in their home country. Forced or coerced returns violate international standards and risk creating instability.

Ensuring the safety and sustainability of returns for Syrian refugees necessitates meticulous planning and international collaboration. A well-structured approach must address critical areas such as security, infrastructure, economic revitalization, legal frameworks, and international support to guarantee the success of large-scale repatriation.

The UNHCR’s 2018 Comprehensive Protection and Solution Strategy (CPSS) provides crucial guidance through its Protection Thresholds and Parameters for Refugee Return to Syria. The strategy outlines 22 specific protection parameters that should be met before transitioning from self-organized returns to large-scale voluntary repatriation operations. These parameters encompass various aspects, including physical security, legal safeguards, property rights, civil documentation, and access to basic services. Current assessments indicate that many of these crucial parameters remain unfulfilled, suggesting conditions may not yet support organized large-scale returns. This gap between existing conditions and international protection standards adds another layer of complexity to individual return decisions and institutional response planning.

The HTS’s designation as a terrorist organization by various international actors creates multiple layers of complications. This designation impacts diplomatic engagement and reconstruction funding and raises questions about the legitimacy of administrative structures and legal proceedings in HTS-controlled areas.

Key Actors and their Preliminary Positions

In Türkiye, President Erdoğan’s recent statement, “As peace takes root in Syria, I believe the number of voluntary returns will increase over time”, reflects a nuanced understanding of return migration dynamics. Turkish authorities have responded to the situation with a measured approach. Border processing capacity has been increased to handle up to 20,000 daily transactions, with additional personnel and mobile units deployed to expedite return procedures. Officials maintain that while they will facilitate returns for those who choose to leave, they neither force nor prevent movement.

UNHCR has recently released a global level note ‘Position of Returns to the Syrian Arab Republic’, providing interim legal perspectives on issues including voluntary returns, forced returns, protection status, and access to asylum. According to this note and considering the volatile situation in Syria, UNHCR does not promote large-scale voluntary repatriation to Syria for the time being and strongly calls on States to respect the principle of non-refoulment at all times.

Across the EU, there is a cautious acknowledgement of Syria’s changing political landscape but no consensus on immediate large-scale returns. The European Commission maintains that the conditions for safe, voluntary, and dignified returns are not currently met, even after the fall of the Assad regime, underscoring the EU’s general position that any repatriation must respect international protection standards. While some member states—such as Austria—have begun incentivizing voluntary returns with financial support, and Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Finland, Ireland, Sweden and non-EU country Norway suspended asylum applications in anticipation of improved stability since the fall of the regime, key voices in Germany and within the Commission have reiterated the need for careful evaluation. They emphasize that returns should be coordinated with EU partners and the UN and must not jeopardize ongoing efforts to ensure Syria’s territorial integrity and the protection of minority groups. High-level diplomacy, including the visit of Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who committed for 1 billion EUR package for the refugee situation in Turkiye, including support for voluntary return, reflects the EU’s intent to engage regionally and shape a collective, measured response. Despite some internal debates—especially with conservative parties urging early returns—the dominant EU narrative remains one of measured optimism coupled with a commitment to ensuring that any future movements of Syrian refugees occur under conditions that uphold safety, human rights, and long-term stability.

Conclusion

Looking ahead, the success of any large-scale return process will depend on multiple factors evolving favourably. Security stabilization, infrastructure rehabilitation, and the establishment of reliable governance structures remain crucial prerequisites. The international community’s role in monitoring conditions and supporting reconstruction efforts will be vital for creating conditions conducive to sustainable returns.

The prevailing environment of “hopeful uncertainty” accurately characterizes the current situation. While the political transition creates new possibilities, most refugees are waiting for tangible improvements in security and living conditions before committing to permanent return. Many families, particularly those with children in Turkish schools, are deferring decisions until at least summer 2025, allowing time to evaluate how conditions in Syria evolve. This is exacerbated by the fact that return is non-reversible, as their TPID would be taken away.

The path forward requires sustained attention to both immediate practical needs and longer-term sustainability considerations. As the situation continues to develop, careful monitoring of conditions, transparent information sharing, and maintenance of protection standards will be crucial for ensuring that any returns remain voluntary, safe, and dignified. The coming months will be critical in determining whether the current political transition can translate into the stable conditions necessary for sustainable refugee returns.

The UNHCR’s recommendation for “go-and-see” visits represents an important practice in supporting informed decision-making. These visits would allow refugees to assess conditions in their areas of origin without losing their legal status in Türkiye, helping bridge the gap between anticipation and reality. However, implementing such programs requires careful coordination between Turkish authorities, international organizations, and Syrian authorities.

Further research is required to understand the implications of the recent changes in Syria and the dynamics of refugee returns. Regarding security and stability, research must assess the actual safety conditions, including the risks of renewed violence, governance capacity, and the effectiveness of justice mechanisms to address grievances and crimes committed during the conflict. Another essential focus is on returnee perspectives. Studies should explore the factors influencing refugees’ decisions to return or remain abroad, their experiences reintegrating into communities, and the psychological impacts of displacement and trauma. Emphasis should also be placed on community acceptance and access to basic services, which are critical for successful reintegration. The rebuilding of social dynamics and infrastructure is another priority. Reconciliation efforts in areas with diverse populations, barriers to social integration, and the reconstruction of housing, healthcare, education, and essential services must all be evaluated to meet the needs of returnees. Addressing legal and administrative barriers is also critical. Research must examine processes for property restitution, the issuance of civil documentation, and the adequacy of legal frameworks governing voluntary and involuntary returns to ensure they align with international standards.

Contact:

Umutcan Yüksel, Researcher (GAPs Project) | Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul (SRII) | umutcan.yuksel@sri.org.tr

N. Ela Gökalp-Aras, Senior Researcher and Principal Investigator (GAPs Project) | Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul (SRII) | ela.gokalparas@sri.org.tr