The Role of Infrastructure Investments in the Return of Syrian Refugees: The Case of Turkish Military Operations in Northern Syria

Map 1: Turkish Military Operations and Border Crossing Points (Source: iMMAP, 2023)

by: Umutcan Yüksel, Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul (SRII)

Türkiye is the largest host and transit country for refugees on the eastern Mediterranean route to Europe. It hosts 3.2 million Syrian refugees and 260,000 non-Syrian refugees, including Afghans, Pakistanis, and Iraqis under International Protection. Initially adopting a welcoming policy, Türkiye has gradually implemented more closed-door and restrictive measures due to security threats and worsening social cohesion which have also impacted the domestic political arena.

To navigate this intricate web of domestic and foreign policy challenges, underpinned by ideational and security considerations, Türkiye has implemented a variety of governance practices including the recent deployment of mobile migration units and the enhancement of the Law on Foreigners and International Protection in 2019, regulating voluntary returns, offering alternatives to administrative detention, return counselling, and coordinated international cooperation. These practices aim to ensure border security, deter irregular migration, address mass movements of refugees, promote return migration, and prevent social tensions. Due to Syria being not a safe country for principled return, Türkiye commits to comply with the non-refoulement principle. However, there are three major types of ad-hoc practices it implements to encourage the return of Syrian refugees:

Allowing and facilitating go-and-see visits during religious holidays in Syria: Between 2017 and 2019, Türkiye allowed Syrians to undertake temporary ‘go-and-see’ visits to Syria (up to three months) during major religious holidays. These visits, while allowing refugees to assess their properties and the security situation, have also sparked debates within the host community, raising questions about the feasibility of permanent returns to Syria. Due to increased media attention as well as COVID-19, the practice was suspended in 2020.

Carrying out deportation operations: Türkiye’s strategic priority to combat irregular migration has been affecting the overall protection environment for refugees. Limitation the rights and entitlements offered through the Temporary Protection in the province of registration, carrying out regular address verification exercises and security checks, closure of 1169 neighbourhoods where the proportion of refugee population is higher than 25% in 2022, and 2019 provincial relocation operation were micro practices that increased the likelihood of Syrians signing voluntary return forms forcibly potentially at the detention or removal centres. Human Rights Watch reported that Turkish authorities arbitrarily arrested, detained, and deported hundreds of Syrian men and boys to Syria between February and July 2022. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, more than 950 Syrians, including women and children, have been forcibly deported from Türkiye since the beginning of July 2023.

Cross-Border control and investments in Syria to improve the conditions and promote return: Türkiye implemented three major military operations (in 2016, 2018, and 2019) that specifically aimed to prevent the formation of politically autonomous regions along the Turkish border controlled by the Kurdish-dominated YPG militants. On the ground, Türkiye established territorial control over the Azaz/Al-Bab/Jarablus area through Operation Euphrates Shield (OES) in 2016 and over the Afrin area through Operation Olive Branch (OOB) in 2018. Both operations were conducted by a mix of co-opted former Free Syrian Army (FSA) proxies under the notional control of the Syrian National Council (SNC) and direct Turkish military intervention. The third major operation on Syrian territory was Operation Peace Spring, which covered Northeast Syria.

The military operations, rooted in two geopolitical objectives - preventing a PKK-affiliated contiguous land corridor in Syria and mitigating mass migration by addressing in-country humanitarian needs - have stirred discussions about their legality under international humanitarian law. On the other hand, this blog post delves into the impact of Türkiye’s infrastructural investments in these areas for the return of Syrian refugees. This topic gains significance against the backdrop of increasing rhetoric by the country’s ruling party, aiming to ensure the return and resettlement of Syrians within Syria, as underscored by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who mentioned a collaboration with Qatar to enable the return of 1 million people within few years in a balcony speech after being re-elected.

Reconstruction and Development Initiatives by Türkiye

Beyond deterring the security threats at the border through these operations, Türkiye also aimed to establish 460 km length and 30 km debt ‘safe zones’ in order to repatriate Syrian refugees in these areas. While the goal of these military operations cannot be only linked to the return objective, the Government of Türkiye has initiated various reconstruction and development initiatives addressing shelter needs by establishing brick houses, restoring municipal and social services, and improving infrastructure and security to promote the return of Syrian refugees.

The investments and the way they are represented in the national media are also quite an important aspect to scrutinise. Linking its return objective with the improvement efforts in Syria, official statements served the strategic narrative to address any mass migration movements inside Syria and to promote return of Syrian refugees. For this purpose, the number of Syrian returnees and improvement and development efforts inside Northern Syria have taken place holistically in the majority of the official statements, indicating an important sign for a turn from discourse to practice. Turkish agencies in cooperation with local councils have provided services in and outside of IDP camps through rebuilding numerous hospitals and healthcare facilities, catering to urgent medical needs and offering specialised care. In education, it implemented various projects ranging from early education to higher education, including setting up schools and university branches. Economically, it integrated the region into its market, particularly in the agricultural sector, and facilitated transit for local producers to reach international markets. Security efforts included training and equipping local law enforcement and establishing observation posts for maintaining peace. Municipal and social services saw the deployment of social workers and rehabilitation of essential infrastructure like water and electricity supplies. Significant progress were made in providing shelter, with thousands of brick houses built for displaced Syrians, in collaboration with international partners such as Qatar and Germany. Finally, its involvement in infrastructure has been pivotal in rebuilding roads and managing camps for internally displaced people, enhancing the region's overall connectivity and living conditions.

With the central authorities’ adaptation in the governing system, district governors/deputy governors are responsible for the investments and any developments in Turkish controlled areas. AFAD plays a vital role as they run Internally Displaced People (IDP) Camps in North West Syria and coordinate with OCHA and other key humanitarian donors for Syria Cross-Border Humanitarian Fund. The Turkish Red Crescent is another significant actor with humanitarian assistance, as well as commercial and humanitarian transfer of goods and materials through the allowed border gates. Lastly, NGOs, construction agencies including Housing Development Administration (TOKI), and post offices are other key actors in the investments.

Return of Syrian Refugees

While ongoing challenges of protracted displacement may motivate some refugees to return, most are deterred by the wide scale destruction and lack of economic opportunities in their areas of origin. However, over the years, returns have been occurring. Return of Syrian refugees is processed with voluntary return form with the presence of Presidency of Migration Management (PMM), UNHCR, civil society and completed with the cessation of the Temporary Protection Status. Where temporary protection is terminated based on cessation, PMM issues a “V87” code to mark the person as a “voluntarily returned foreigner”. The person is usually left at the border and handles the return process for him or herself. However, beneficiaries are not always adequately informed of the process. Moreover, the aforementioned interview procedure is not followed in Removal Centres. Persons signing voluntary return documents – often following pressure from authorities under detention - do not undergo an interview by a panel aimed at establishing whether return is voluntary.

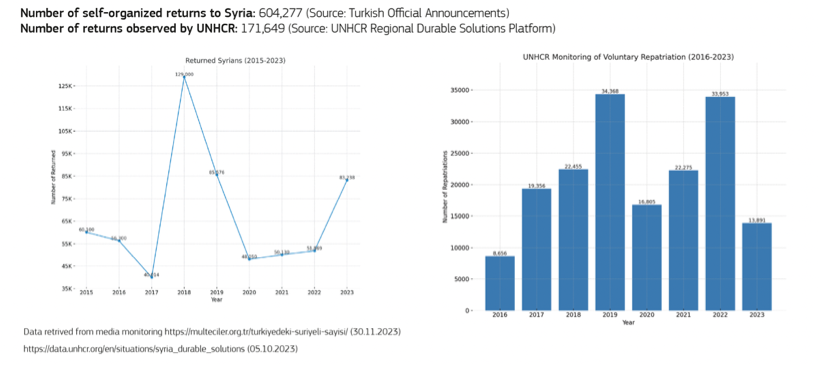

Turkish officials frequently share the numbers of Syrian returnees. On December 17, 2023, the Minister of Interior announced that 604,277 Syrians had returned to their homes since 2016. While these figures should be approached with caution, they also indicate an increasing trend of voluntary return discourse among the Turkish political elites, which also align with the field practice. Graph-1 shows that annual voluntary return figures vary between 40-60 thousand. However, there was a peak in 2018-2019, indicating the potential impact of i) narrative highlighting improved conditions through the military and ii) irregular migration operations and shrinking protective environment through detention and forced return practices (e.g. provincial relocation projects, address verification exercises, etc.) Similarly, another increase was observed in 2023, potentially linked to the February 2023 earthquake in Türkiye and Syria, which resulted in the voluntary return of 42,000 Syrians. Increase in the anti-refugee sentiments have also had an impact on the return decisions. Aside from the Turkish official statements, UNHCR has a role in observing the voluntary nature of the returns. Accordingly, it has participated in the voluntary return interviews of 171,649 Syrians since 2016.

Graph 1: Number of Voluntary Return Figures Extracted Based on Tracing Turkish Official Statements and the UNHCR Durable Solutions Platform

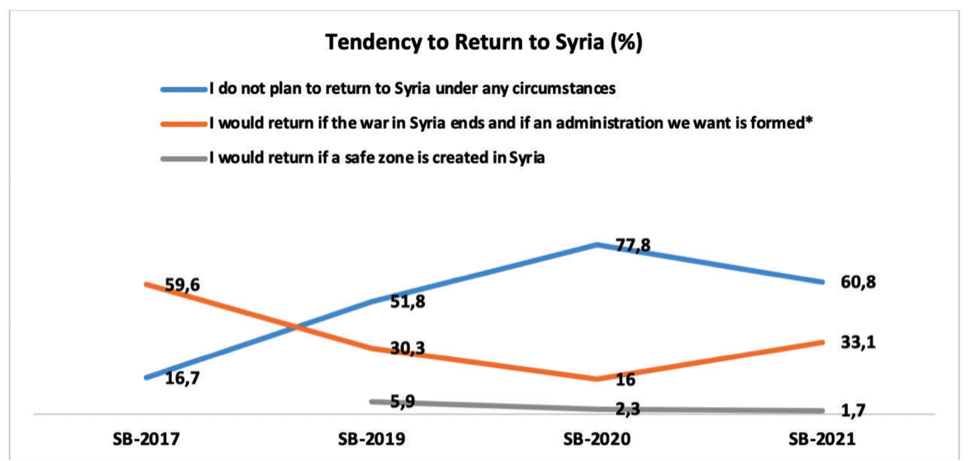

UNHCR has not conducted any intention survey in Türkiye yet, despite the return perceptions and intentions of refugees in other neighbouring countries were reflected through the eight regional surveys. The only publicly available information on refugees’ intention to return is from Syrians Barometer (SB) studies conducted by Prof. Murat Erdogan over the years. Accordingly, the top response in SB-2021 was “I don’t plan to return to Syria under any circumstances”, as it was in SB-2019 and SB-2020. However, while the rate of this answer was 16,7% in SB-2017, it dramatically increased to 51,8% in SB-2019 and further increased once again to 77,8% in SB-2020. However, this figure strikingly dropped to 60,8% in SB-2021, by decreasing 17% compared to 2020. This 17-point drop was directed towards the second option, “I would return if the war in Syria ends and if an administration we want is formed.”. However, despite all of this, two clear points among the Syrians are that over 60% of the participants do not want to return at all, and they almost never want to return to the “safe zones”. These show that the “voluntary return” tendencies of Syrians are still not sufficiently strong enough to bring about serious change.

In February 2022, the Minister of Interior announced the intention survey carried out with national resources. Accordingly, 12% reported their intention to return if a safe zone was established within North West Syria. 4.1% would return if the conflict continued. Concluding from these figures, 16.1% (approximately 600,000 individuals) would potentially be willing to return. The question is whether the 4,1% who responded that they would return regardless of the conditions are the same group as those who have returned as observed by UNHCR (approximately 20,000 a year). The large group of undecided individuals (38%) would likely consider alternative solutions, ranking return as the last option. About 440,000 persons (12%) would be ready to return to the safe zones. However, relocating them in the medium-term does not seem feasible, particularly considering the challenging humanitarian environment and the large number of IDPs in the areas controlled by the opposition.

Graph 2: Tendency to Return to Syria (Source: Syrians Barometer 2021)

Conclusion

UNHCR's stance on the current situation in Syria reflects a reality unsuitable for safe and dignified voluntary return due to human rights violations, conflict, and a lack of rule of law. Organized return operations, requiring a legal framework to protect returnees, clear evidence of safety, improved local conditions, and refugee requests for assistance, are not feasible yet. The Global Protection Cluster's analysis reveals significant challenges in Northwest Syria, including human rights abuses, gender-based violence, and barriers to basic rights and services, making the region unfit for returns. While Türkiye's infrastructure investments have somewhat improved conditions for the internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the region, these efforts have altered the ethnic/demographic changes as well as further displacement within Syria. Therefore, it is vital that any policies and strategies for managing refugee returns align with the actual needs and desires of the refugee community, as well as the international norms and standards.

Contact:

Umutcan Yüksel, Researcher (GAPs Project) | Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul (SRII) | umutcan.yuksel@sri.org.tr