Dynamics, environment and migration interface in Nigeria

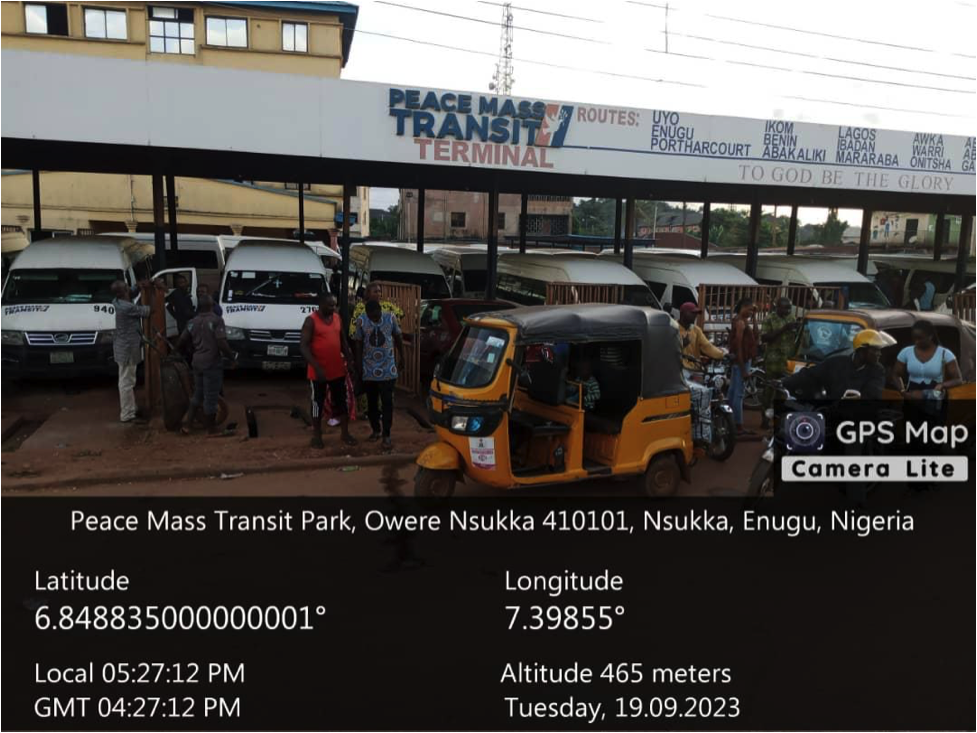

An image taken at Peace Mass Transit Park, Owere Nsukka, Nigeria

by: Ngozi Louis Uzomah, Ignatius A. Madu, Chukwuedozie K. Ajaero | University of Nigeria

Dynamics of migration in Nigeria

Nigeria is the largest economy in Africa and as a result, it attracts migrants from various countries in the African continent who migrate to seek better economic prospects and/or refuge from conflicts. The movement into Nigeria became prominent in the late 1970s and early 1980s when many West Africans arrived seeking employment (Yeboah, 1986). In the last two decades, migrants from Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan who are fleeing conflicts in their countries have been added to the list. Both the African Union and ECOWAS free movement protocols provide the legal basis for such mixed migration (Okunade & Ogunnubi, 2019; Arhin-Sam et al., 2022). Many of the migrants use Nigeria as a transit to other parts of the world including France, Belgium, Germany and Spain.

When the economy of Nigeria gradually deteriorated in the early 1990s, its citizens joined other Africans in aspiring to emigrate out of the continent. While the main driver to migrate from Nigeria was to seek education in the UK and the USA in the 1960s/70s, in the 1990s, this started to include economic reasons to countries such as Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Spain and Italy and later UAE, China and Malaysia. Many of these migrants succeed in regularly sending remittances home and intermittently pay visits to their home country during which they display economic buoyancy.

As a result, younger Nigerian youth gets attracted to what they perceive as greener pastures abroad stimulating their aspiration to migrate. However, most Nigerians who aspire to migrate are constrained by their inability to procure visas. This piece sought to showcase social, political and economic conditions in Nigeria that drive migration aspirations as well as financial cost, administrative difficulties and lack of humanitarian corridors as factors that influence migration aspirations in Nigeria.

Emigration environment and aspiration to migrate from Nigeria

Migration aspirations are formed within the context of what Carling (2001) calls the emigration environment. This consists of the economic, socio-political and environmental conditions at all levels as they relate to the social context of the people in the migration project. Regarding the local emigration environment, the aspiration to migrate is fueled by challenges of bad governance orchestrated by corrupt and greedy politicians who stash funds, meant for the socioeconomic development of Nigeria, in foreign banks. Furthermore, the activities of jihadists and separatists create a crisis situation that prompts Nigerians to flee. In addition, election manipulation generates discontent among Nigerian voters as their will to choose legitimate leaders is thwarted by electoral malpractices, assassinations and intimidations which are common occurrences in the country (ADST, 2015; Premium Times, 2014). A recent case is the 2023 general election results which were rejected by the three major opposition political parties (Obiezu, 2023). Though the EU Report condemned the process, the election petition tribunal ruled in favor of the current president as the winner of the 2023 presidential election. Many Nigerians especially the youths were disappointed with the verdict, feeling hopeless and hapless which, in no doubt, is a recipe for emigration.

In terms of destination countries’ emigration environment, the combination of perceived job availability, good living standard and respect for democratic values in countries such as the USA, Germany, Switzerland, the UAE and the Netherlands attracts many Nigerians. There are also discursively constructed ideas of a utopian life abroad which are mostly riddled with imperfect information. For example, when stories of economically stable Europe and commercially bustling American cities are narrated, there is no mention of the job accessibility difficulties, homelessness, culture shocks, harsh winter weather, racism and discrimination faced by immigrants. Even when the news is available in the media, it is perceived as non-significant but surmountable challenges that pale in comparison to the deplorable socioeconomic and political situation of Nigeria and cannot deter ardent aspirations to migrate. This has generated a social phenomenon known as the Japa syndrome - a Yoruba word meaning leaving for greener pastures. It is an attitude adopted by frustrated Nigerians, mostly youths, who are dissatisfied with the socioeconomic and political situation in Nigeria and are anxious to emigrate for a better life. However, in reality, most of them remain in a situation of involuntary immobility constrained by barriers to migrate.

Another image taken at Peace Mass Transit Park, Owere Nsukka, Nigeria by GPS Map

Peace Mass Transit Terminal, Nsukka, one of the local motor parks in Nigeria from which migrants using irregular pathways initially board buses to Lagos and Kano (major migrants’ collection hubs) before boarding another one to Agadez (Niger Rep), Cotonou (Benin Rep) or Bamako (Mali) for onward movement to countries in the Maghreb in a bid to enter Europe.

Immigration interface and ability of Nigerians to migrate abroad

The ability to migrate according to Carling & Schewel (2018) is constrained at the immigration interface. The immigration interface in Nigeria consists of barriers such as financial cost for procuring travel documents, administrative difficulties in visa procurement as well as lack of humanitarian corridors to achieve migration aspirations. Desperate Nigerians sell family properties to raise money for their migration project. They pay up to US$ 24.000 to smugglers to get to Europe (The Migrant Project, 2023). Due to little or no legal pathways to migration, some pay GBP10.000 to labor recruitment agencies to help them procure visas. Once there, as they struggle to secure employment, they end up relying on food banks in countries such as the UK (Daily Trust, 2023). Additionally, most Nigerians who aspire to migrate do not have the substantial amount needed for visa procurement and there is no international resettlement program for Nigerians who are fleeing conflicts. The combination of these creates a situation of involuntary immobility among Nigerians.

Most importantly, Nigerians who have the financial wherewithal to migrate but are unable to procure visas engage in clandestine movement, from their villages and towns, to achieve their aspirations. Unfortunately for them, the Law No 36 of 2015 in neighboring Niger Republic makes it extremely difficult to travel through the country. They and those in solidarity with them including motorists, food vendors and facilitators are criminalized. Migrants who escape this stage face robbery, attacks and death by dehydration in the Sahara Desert, police brutality in Algeria, xenophobia in Tunisia or might become victims of trafficking in Libya. The ‘lucky’ ones are extorted by smugglers who get them into life-threatening dinghies to cross the Mediterranean Sea where many lose their lives (Uzomah, 2021), to harsh sea currents and deadly push backs from the EU and its Member States’ Coast Guards or that of Libya and Tunisia. In both cases the migrants realize too late that all that glitters is not gold and that migration aspiration is far from reality. The earlier this reality is communicated to the intending migrants, the better for them, the country, and the European Union.

References

ADST (2015, December 30). The Stolen Victory and Mysterious Death of Moshood Abiola. https://adst.org/2015/12/the-stolen-victory-and-mysterious-death-of-moshood-abiola/

Arhin-Sam, K., Bisong, A., Jegen, L., Mounkaila, H. & Zanker, F. (2022). The (in)formality of mobility in the ECOWAS region: The paradoxes of free movement, South African Journal of International Affairs, 29:2, 187-205, DOI: 10.1080/10220461.2022.2084452

Carling, J. (2001). Aspiration and Ability in International Migration Cape Verdean Experiences of Mobility and Immobility. Published Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oslo. Retrieved from https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/136983/2001_09_Aspiration_Ability_International_Migration.pdf

Carling, J. & Schewel, K. (2018). Revisiting Aspiration and Ability in International Migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384146.

Okunade, S. K., & Ogunnubi, O. (2019). The African Union Protocol on Free Movement: A Panacea to End Border Porosity? Journal of African Union Studies, 8(1), 73–91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26890418

Premium Times (2014, April 8). The election that brought Yar’Adua to power a huge embarrassment, says Jonathan. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/158357-election-brought-yaradua-power-huge-embarrassment-says-jonathan.html?tztc=1

The Migrant Project (2023). Irregular migration to Europe: what is the cost for Nigerians? https://www.themigrantproject.org/nigeria/irregular-migration-to-europe/

Uzomah, N. L. (2021). Failing Nigeria once again – Views on the EU’s New Pact for Migration and Asylum from Nigeria. https://migration-control.info/en/blog/views-on-the-new-pact-from-nigeria/

Yeboah, Y. F. (1986). The crisis of international migration in an integrating West Africa: A Case Study of Nigeria and Ghana. Africa Development / Afrique et Développement, 11(4), 217–256. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24486623

Contact:

Ngozi Louis Uzomah | University of Nigeria, Nsukka | ngozilouisuzomah@gmail.com

Prof I. A. Madu | University of Nigeria, Nsukka | ignatius.madu@unn.edu.ng

Prof C. K. Ajaero| University of Nigeria, Nsukka | chukwuedozie.ajaero@unn.edu.ng